King Ian

Let us now praise British actors.

I am a fan in general of Brit thespians and, of course, of the Irish, but I have a particular fondness for the English. Maybe it has something to do with the supposed inferiority complex many of us Yanks have about the way we speak the language compared to how people in perfidious Albion speak it. Maybe it is indoctrination from watching too many BBC productions on public television in my youth.

Over the years I have witnessed enough live interviews with actors to fancy that I have something of an outsider’s appreciation of the acting craft and even to make generalizations about the difference between British and American ones. The best summation of that difference was one I heard from Jeremy Irons in 2007 at the Galway Film Fleadh. Here is how I noted it at the time: “American method acting involves the actor actually producing the emotion, sometimes getting their fellow cast members to help provoke them into the right state. The English actor simply calls up the emotion from inside himself. Irons likened himself to a piano, with many keys but only a few of which are actually played in real life. Acting, he said, allowed him to play other keys that he would never use in normal life—like, for example, the part of him that could be, in theory at least, a murderer. Whereas some American actors talk about how they have trouble getting out of a role they have immersed themselves in and can’t leave it at the studio, Irons insisted that never happened to him.”

Over the years I have witnessed enough live interviews with actors to fancy that I have something of an outsider’s appreciation of the acting craft and even to make generalizations about the difference between British and American ones. The best summation of that difference was one I heard from Jeremy Irons in 2007 at the Galway Film Fleadh. Here is how I noted it at the time: “American method acting involves the actor actually producing the emotion, sometimes getting their fellow cast members to help provoke them into the right state. The English actor simply calls up the emotion from inside himself. Irons likened himself to a piano, with many keys but only a few of which are actually played in real life. Acting, he said, allowed him to play other keys that he would never use in normal life—like, for example, the part of him that could be, in theory at least, a murderer. Whereas some American actors talk about how they have trouble getting out of a role they have immersed themselves in and can’t leave it at the studio, Irons insisted that never happened to him.”

I fully believe that these different approaches lead directly to English actors having a healthy attitude to their work and, by extension, to their audiences. In contrast, American actors, especially the really successful ones, can be really full of themselves. I am in constant amazement how genuinely nice and thoughtful the Brits seem—even the most lauded and celebrated ones.

Speaking of Jeremy Irons, I happened to see his wife last week. Sinéad Cusack was appearing in a production of Shakespeare’s King Lear at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London. She played the Earl of Kent, one of the few characters to remain steadfastly loyal to the king in spite of his madness. The role was written for a man, but since she ends up disguising himself as a common man called Caius, the gender switch actually works quite well.

The lead role was played by none other than Sir Ian McKellen and, as you would expect, he did a magnificent job. In this production the role is quite strenuous. At one point he is drenched for a good long period by falling rain, and I could not help thinking it would be a miracle if he got through the run without a bout of pneumonia. The man will turn 80 next May, and he put me to shame for my occasional thoughts of maybe taking it easier because of my (much younger) age.

It had been years since I had been to a theater in London, and it was a delightful reminder of what a wonderful, if somewhat pricey, experience it is. There is nothing like a live performance—after years of mostly consuming entertainment on screens—to give you a fresh appreciation for the arts of set design, direction and acting. And nothing enhances the experience more than sharing it with an appreciative audience.

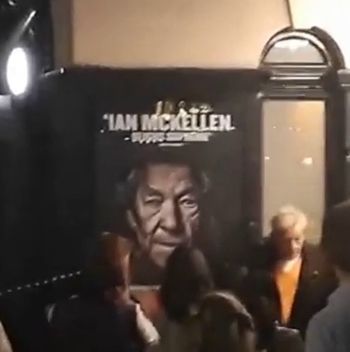

Abuzz and enthused by what we had seen, we made our way out of the theater. My inclination was race the crowds for a place in one of the many West End eating and drinking establishments throbbing with people and energy at 11 o’clock at night. We noticed, however, that many of our fellow audience members were gathered around the side of the building, waiting for the actors to emerge, so we hung around too. Every few minutes one or two would appear. Heroes, villains, earls, ladies, kings and even a fool strolled through the crowd and down the street, looking everyday and ordinary in their jeans with their rucksacks slung over a shoulder. Inside they had all gotten a standing ovation, and now some got an additional smattering of applause. Finally, McKellen himself arrived, looking tired but game, to the most enthusiastic clapping.

Abuzz and enthused by what we had seen, we made our way out of the theater. My inclination was race the crowds for a place in one of the many West End eating and drinking establishments throbbing with people and energy at 11 o’clock at night. We noticed, however, that many of our fellow audience members were gathered around the side of the building, waiting for the actors to emerge, so we hung around too. Every few minutes one or two would appear. Heroes, villains, earls, ladies, kings and even a fool strolled through the crowd and down the street, looking everyday and ordinary in their jeans with their rucksacks slung over a shoulder. Inside they had all gotten a standing ovation, and now some got an additional smattering of applause. Finally, McKellen himself arrived, looking tired but game, to the most enthusiastic clapping.

There was a solid-looking minder to keep the crowd from smothering him. I assumed the actor would be whisked away into a nearby car or perhaps into a taxi but, no, he made a point to sign every program that was put in front of him and to hear everyone who wanted to speak to him. My God, I thought, after laboring for four hours through five acts, he is committing himself to a virtual sixth act of fan interaction. What a gentleman!

My own progeny, though shy, went forward for her own autograph, and I found myself doing something I usually successfully resist. I recorded video with my phone. On viewing it later, I was delighted to see that the big screen’s Gandalf was not wearing tony tweeds, as I might have expected, but a Hobbit jumper!

My kid recently finished a year of studying Lear for the state exam in English that is part of the dreaded Irish Leaving Certificate, the culmination of her secondary education. By this point she had seen numerous productions on big and small screens and on stage so, as her moment came, it was not mere idle gushing when she told him, “You were the best King Lear I have seen.” Perhaps he was amused by such judgment from one so young but, if so, he showed no sign.

“May you see many more,” he replied graciously.

As far as I could see, he attended to every last person who stood there waiting. Then, with no fuss or fanfare, he slipped away modestly into the London night.

-S.L., 24 August 2018

If you would like to respond to this commentary or to anything else on this web site, please send a message to feedback@scottsmovies.com. Messages sent to this address will be considered for publishing on the Feedback Page without attribution. (That means your name, email address or anything else that might identify you won’t be included.) Messages published will be at my discretion and subject to editing. But I promise not to leave something out just because it’s unflattering.

If you would like to send me a message but not have it considered for publishing, you can send it to scott@scottsmovies.com.